As Bangladesh gears up for its upcoming parliamentary elections, a study by Digitally Right has laid significant shortcomings in Meta’s political advertising enforcement. The study, titled “Hits and Misses: An Examination of Meta’s Political Ad Policy Enforcement in Bangladesh,” published today (Monday), finds various active political ads, lacking required disclaimers, managed to slip through Meta’s detection systems.

The study also finds issues of over-enforcement, with non-political ads facing inaccurate categorization, disproportionately affecting commercial entities. The inadvertent mislabeling, ranging from product promotions to employment services, prompts questions about the efficacy of Meta’s ad classification algorithms.

It reveals instances of incomplete or vague information in disclaimers provided by the advertisers that falls short of Meta’s transparency standards and hints at potential gaps in the platform’s verification processes leaving users in the dark about the sources funding political advertisements.

Political advertisements significantly impact democratic processes by shaping public perceptions of political systems and leadership and function as the most dominant form of communication between voters and candidates before elections. And social media has brought about a significant transformation in electoral campaigns, enabling political actors to engage with a vast audience through advertisements.

In January 2023, Bangladesh had 44.7 million social media users, representing 34.5% of the population aged 18 and above, as reported by Data Reportal. Among these users, Facebook stood out with the highest number, accounting for 43.25 million. Among the major platforms only Meta, in its Ad Library, offers disclosures on ads related to election, politics and social issues — that his study terms as political ads. It allows an opportunity to scrutinize the identity of advertisers, amount spent and content of such ads.

The study analyzed detected political ads and related disclaimer information available in the Meta Ad Library in one year period and ran keyword search to identify active but undetected political ads.

Political but Undetected

The under-enforcement undermines the entire purpose of political ad transparency as it represents a failure of the transparency system, which then leads to missing significant portions of political advertising on the platform.

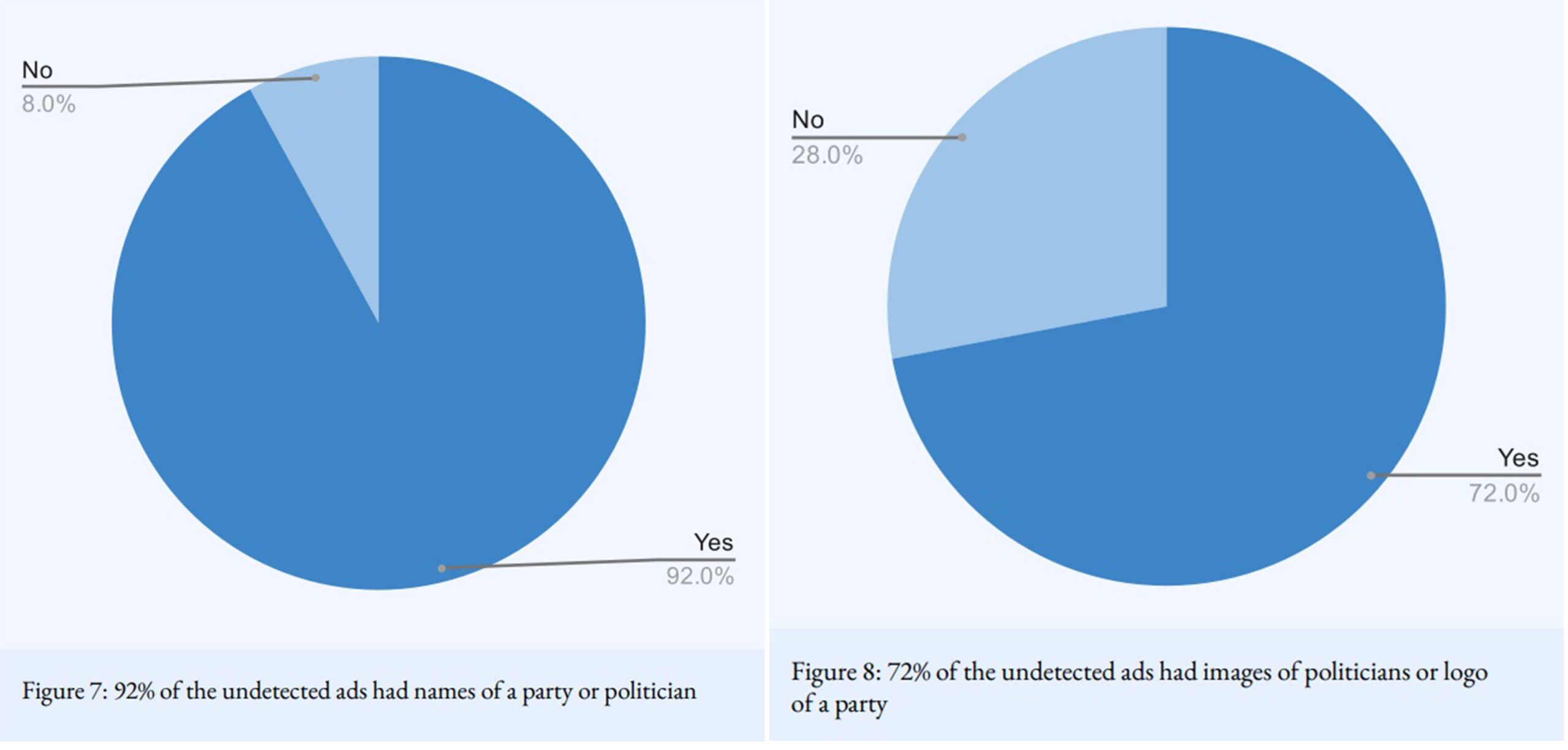

The study finds 50 active ads with clear political messages and almost half of those ads came straight from political figures and parties highlighting underenforcement. Over 90% of the undetected ads prominently displayed political party names or political figures in the text and 72% included photos of political leaders or party symbols. These ads were found by keyword search for just four days within the research period.

According to the findings, identical ads were identified as political when shared by certain pages but not when posted by others. Political demands featured on ostensibly unrelated pages bypassed detection at least in five cases. It also finds a delayed response in identifying and flagging political ads, with instances of ads running for prolonged periods without disclaimers. For instance, an ad conveying a political message remained undetected for a staggering 372 days despite accumulating a million impressions.

Advertisers Evading Transparency

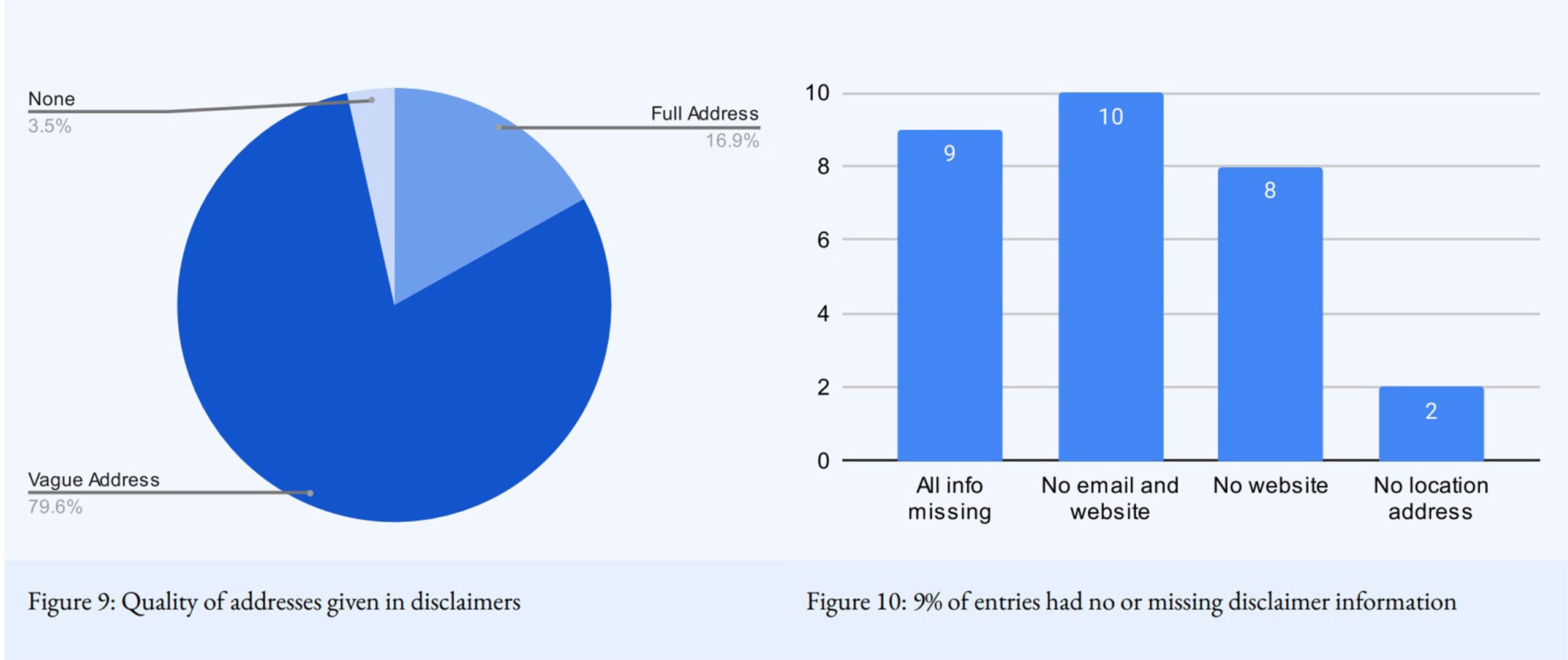

The study analyzed 314 “paid for by” disclaimers available in the Ad Library and found that nine advertisers, including a mayoral election candidate and two politicians, didn’t submit any required transparency information yet were allowed to display political ads.

Meta advertising guidelines require the advertisers to provide phone, email, website, and location addresses that are functional and correct at all times. However, the study finds, 80% of the 314 disclaimers had ambiguous or insufficient address information, with 47% using only the district name. Only 17% had complete and operational addresses and 58% used a Facebook page URL in lieu of a website.

“Paid For By” disclaimers are at the core of ad transparency and crucial for users because they provide essential information about who is funding and supporting a particular advertisement allowing voters to understand the interests and affiliations behind the messages they encounter. Findings of the study imply that once disclaimer information is provided, there is inadequate effort from meta in verifying “functionality” and “correctness” of the information in disclaimers.

Non-Political but Detected

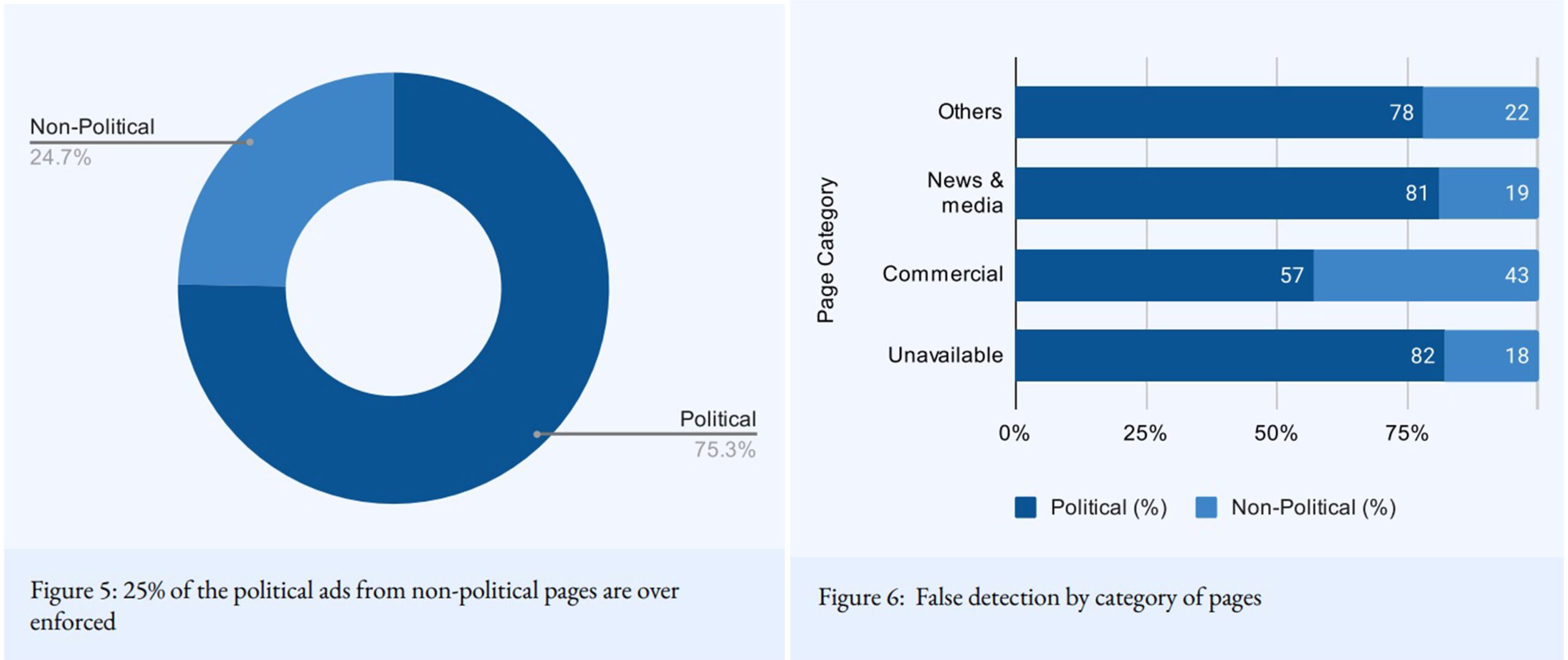

This study analyzed 1,420 advertisement samples from the Ad Library that were posted by pages in the non-political category and found that about 25% of the advertisements from non-political pages (i.e., commercial, news and media, and other categories) were incorrectly detected as political. The highest rate of false positives (i.e., ads erroneously identified), at 43%, occurred in the ‘commercial’ pages category, indicating that it was the most adversely impacted by over-enforcement.

The study identified mis-detections where ads from commercial pages owned by political figures were inaccurately labeled as political. Even simple product promotions from companies owned by political figures faced incorrect categorization.

Ads promoting the sale of guidebooks, textbooks, novels, and services related to employment opportunities, studying abroad, and visa applications were detected as political, seemingly for being considered as a social issue, highlighting a need for more precise classification of social issues for Bangladesh.

Commercial pages encountered challenges stemming from keyword-related issues, where seemingly innocuous terms like ‘Minister’ triggered the misclassification of electronic appliance advertisements and marriage matchmaking services as political ads.

Keywords such as ‘winner’ and references to specific events further contributed to the misclassification of ads, underscoring the complexities in accurately categorizing content on the platform.

Recommendations

This study’s findings underline crucial areas requiring attention and improvement in ensuring transparency within online political advertising for Bangladesh.

Recommendations from the study, informed by expert interviews, highlight the necessity for Election Commission mandated regulations, regular audits of keywords by digital platforms, and stronger collaboration between various stakeholders for effective oversight.

Here is are some of the key recommendations:

- Social media platforms, such as Meta, must conduct regular audits on keywords tailored to the Bangladeshi context to ensure accurate classifications of political ads and collaborate with stakeholders, including the Election Commission (EC), election watchdogs, researchers, and civil society for context-specific insights and evaluations for the effectiveness of these audits.

- To foster transparency, the Election Commission or government must mandate all social media platforms to disclose political ads data specific to Bangladesh and policies on what information should be made available and how.

- To clarify regulations for online advertising and campaigning in Bangladesh, the Election Commission (EC) guidelines must explicitly include provisions for overseeing online political campaigns and allowing parties to self-disclose all their official pages.

- Meta should collaborate with local stakeholders to establish and publicly disclose a comprehensive list of relevant social issues specific to Bangladesh.

- Meta must display and archive not only political but all ads uniformly, across all jurisdictions, as it does for the EU to comply with the Digital Services Act.

- Social media platforms, including Meta, must invest in more human reviewers with specific knowledge of the local political landscape and language to ensure the effective review of political ads.

This study is an integral component of Digitally Right’s ongoing commitment to exploring the intersection of technology and its impact on society. Digitally Right, a research-focused company at the convergence of media, technology, and rights, provides essential insights and solutions to media, civil society, and industry to help them adapt to a rapidly changing information ecosystem.

The full report is available here.